I’m talking about Torture

I’m talking about Torture

I was a young man longing for freedom, deeply patriotic, and in love with literature. I thought the worldcould be changed. I supported the Iranian Revolution in the fervent belief that green shoots of freedomwould sprout up, no one would go hungry, and dictatorship would be consigned to dusty museums.

But suddenly I found myself in hell. In 1983, arrested in a government crackdown on oppositionparties, I was assigned to the care of a man who was employed as my “interrogator”. I was helplessprey, caught in the trap of the “brothers”. In the Islamic Republic of Iran, “brother” is the generic titleof all male believers, and each of the interrogators were therefore called “brother” and an assumedname. My whole existence lay in the hands of one such brother, “Brother Hamid”. In defendingthe “holy” government, Brother Hamid saw himself as God’s representative, with absolute controlover every aspect of my life. Sleep, medication, food, even going to the toilet, were impossiblewithout his permission. His motivation was hatred based on religious ideology, his tools were a whipand handcuffs. He saw me as a traitor, a spy, the embodiment of corruption and evil. Everything heassumed about me I had to “confess” to, and eventually I did, under the onslaught of brutal whippings,my feet raw and swollen from the lash, strung up from the ceiling of my cell by a rope for days andnights on end, deprived of sleep, of every human dignity, and in torment that my wife was beingtortured too. If I needed anything, I had to bark like a dog. And whenever I barked, Brother Hamidlaughed.

Brother Hamid transformed me from a young idealist to the lowest form of life on earth. After 682days in solitary confinement, subjected to every deprivation, my “confessions” were used, in a showtrial lasting just six minutes, to sentence me to fifteen years in prison. In the mass killings that werecarried out by the government in the summer of 1988, I came very close to being hanged – called upbefore another kangaroo court, I was forced to lie. Each prisoner was asked three questions: Are youa Muslim and say your prayers? Do you renounce your past? Do you believe in the Islamic Republic,and who is your point of reference. And I lied to all three questions. I said I hated my past and wasdevoted to Ayatollah Khomeini, and I was spared the rope. Eventually, after spending six yearsincarcerated in some of the most infamous jails in the Islamic Republic, I was freed to rejoin the mega-prison that is today’s Iran. I escaped in 2003, and am now forced to live in exile.

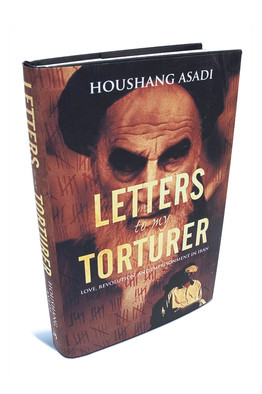

Then one day, a few years ago, someone emailed me an image. He asked if I knew the man in thephoto. I did. It was Brother Hamid, by this time one of Iran’s ambassadors. Staring into his eyes, Iknew I needed to confront my torturer and the living nightmare that was his legacy to me. I searchedthrough my scattered notes, written intermittently over the years since my release from prison, butthey were filled with hatred and I no longer identified with them. I didn’t wish to view the world, asmy torturer had, in black and white terms. I didn’t want to respond to the whip with the sword of mypen. No, now that I was the judge, I hated the idea of taking my revenge on him. Instead, I decidedto write letters to him, to convey to him in some small way the intimate cruelty of those days and theiraftermath.

Writing this book was a painful struggle. Every dawn as I started work on the manuscript, I wouldreturn to Brother Hamid’s hell. I would weep and write and the soles of my feet would throb. I evenhad a heart attack. Every fibre of my being protested, but I forced myself to keep going. I wanted tolay bare the life of a person under torture, and to describe the effect of that torture on the mind andbody of a human being. In the process, I had to overcome my inner turmoil and remove every traceof hatred, line by line. I did my best to view the scene impartially and to be true to myself, as there isnothing more frightening to me than a victim of torture becoming a torturer himself. In the end, I beganto see something of myself in my torturer, and found myself recognizing him as a human being too, asanother person born in the same autocratic culture. And finally I gathered up my letters in this book,which I hope will eventually reach Brother Hamid’s hands, sooner or later. Perhaps he will recognizehimself in these pages.

During my long years in prison, I realised that thousands of men and women, before me, alongside

me, and after me, were tortured to death. I wish the story of torture and imprisonment could end withmy story, and that of Brother Hamid. I wish the history of torture, which follows in the footsteps ofthe inquisitions of the Middle Ages, would end with the Islamic Republic of Iran. But even in recenttimes, from the valleys of Afghanistan to the prison camp of Guantánamo Bay, prisoners have beeninterrogated using techniques that, just fifty years earlier, the US military had condemned for elicitingfalse confessions. And we are all familiar with the sexual degradation and torture of Iraqi prisonersthat was captured in chilling photographs, and appeared on our television screens and in newspapersaround the world.

As I finished the first draft of this book in 2009, Iran descended into political unrest and chaos onceagain. And the people who are protesting against Iran’s autocracy today are sadly being subjected tothe same treatment we were a generation ago, as hundreds of new Brother Hamids keep the torturechambers busy. Young men and women are being tormented using ever more refined techniques ofphysical and psychological manipulation and the application of pain so that they will “confess” to beingspies for the USA and Israel.

In the era when my “Brother Hamid” and his fellow interrogators were torturingpolitical prisoners mercilessly, no one knew about it. It took many years for ourstories to leak out and be heard. Today, torture is still being practised in many partsof the world, but the news travels more quickly. In the current political climate, then,Letters to My Torturer is more than the account of one man’s experience of tor ture. Itis the exploration of an issue that sits heavily on humanity’s conscience.

At the height of one of his torture sessions, Brother Hamid asked me: If one day things change andwe end up being your captives, what will you do to us? My answer is this: we will demolish all theworld’s infamous prisons of torture and we will sentence the intelligence officers and interrogatorsto go to their ruins to plant flowers and sing love songs. And the sham trials, the torture, and allforms of degrading and inhuman treatment that went with them will at last be a thing of the past.